JT: With the quick progress you made with the new strategy, you started buying back shares in late 2022 and you have reviewed your dividend policy. As you know from our 2019 NOYM report How to pay it out, we are really interested in the topic of payouts to owners. Could you share a bit of your thinking on how much capital to distribute to shareholders, and how? Is optimising the cost of capital a key consideration?

PAF: The way we see it, our business has to have a cash flow which is sufficiently good every single year, but then particularly good in the favourable years. Being able to show this profile, even for a cyclical business, should allow us to offer stability in our ordinary dividend. As I said, we understand that investors seem to value this stability, and it is a concrete commitment to return capital. And then we can use other tools to pay capital to our shareholders, as circumstances allow. This year, we proposed our ordinary dividend to be EUR 0.25 per share, and we have also proposed an extra dividend of EUR 0.10. This is on top of the EUR 100m share buyback programme we initiated in November 2022. This gives us flexibility to vary payouts beyond the ordinary dividend we have committed to.

We also need to consider that Outokumpu has an outstanding convertible bond maturing in 2025, which could be converted into some 40 million new shares. The strike price for conversion is around EUR 3, so currently it seems likely that it will be repaid with new shares. This made it even more natural for us to seek a share buyback mandate, as we can use the excess cash we have available to buy the shares we will likely need to repay the bond at maturity. For us, securing this and 'making good' on our higher-leverage past is a priority before pursuing major investments in the final phase of our new strategy.

Cost of capital is of course a factor in our strategy. My CFO brain emphasises that debt has a lower cost than equity, and that there are benefits from having leverage. But it is one out of many considerations, and it comes further down the list after ensuring that our level of financial risk is a good match with the operating leverage and volatility in our business. Despite a negative impact on our cost of capital, we were quite happy to accumulate cash during the COVID-19 pandemic, given the great macroeconomic uncertainty we were facing at the time. There are still significant risks to the economy, but today we consider them more manageable. And this is why we were comfortable launching a EUR 100m share buyback programme.

JT: We have had a decade of ultra-low interest rates and funding costs versus earlier historical levels, and generally strong capital markets. Do you think large corporates have grown accustomed to seeing this as the new normal? Could there be a need to view re-financing, interest rate and liquidity risks in a new light?

PAF: Ten years is a very long time, and there are of course treasury people and CFOs out there who have worked 20 years or more and remember a notion of normal which meant less forgiving market conditions than what we have had in the past decade. It has in many ways been an extraordinary time, and I think it is probably fair to describe it as an addiction we developed, getting used to cheap and ample funding. Cash flow has rarely been a real constraint, and interest rates have almost been a non-issue. Today's environment is totally different. If you have a more strained balance sheet, having to pay interest rates of 7% or 8% will make a real difference in your P&L. The impact becomes so visible that it markedly increases the pressure to deliver cash flow and capital discipline and profitability. And the threshold for it to actually become financially dangerous for the companies is much lower. We will absolutely have to think in new – or old, if you will – ways about what are normal funding market conditions.

I think there is also a tendency out there to expect that this tougher market environment we now face is an anomaly which will pass. It is probably natural and human nature to see something suboptimal as abnormal and temporary, and that normality will be a more favourable state again. But I think it would be risky to simply assume that this will happen. While there may not be further waves of energy or food price inflation, there are other potential drivers for more inflation going forward. Heavily globalised corporate supply chains will likely at least regionalise going forward, as geopolitical tension related to, for example, Russia, Iran and China will not simply vanish. Ever lower cost sourcing may therefore not suppress inflation in the years ahead, like it has for decades historically. We may simply have to get used to a world with a bit more inflation and higher interest rates than we got used to in the past decade.

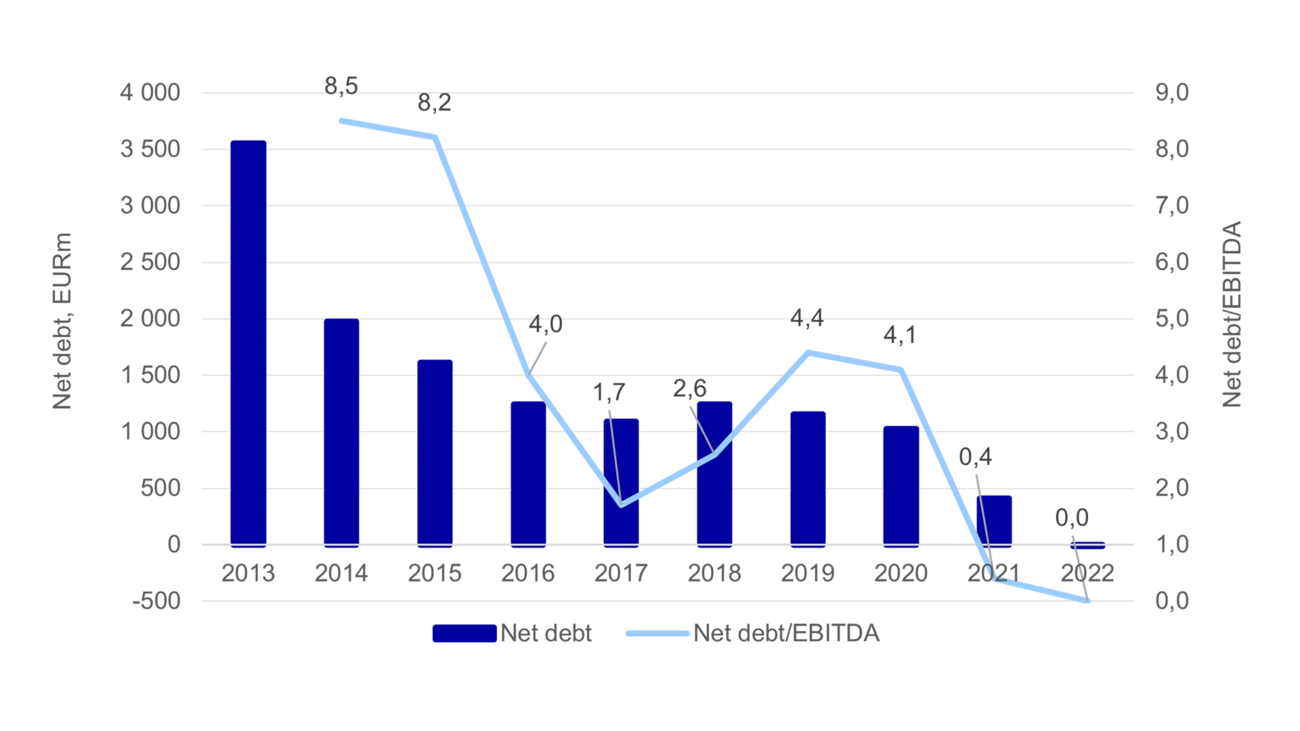

OUTOKUMPU'S NET DEBT AND LEVERAGE