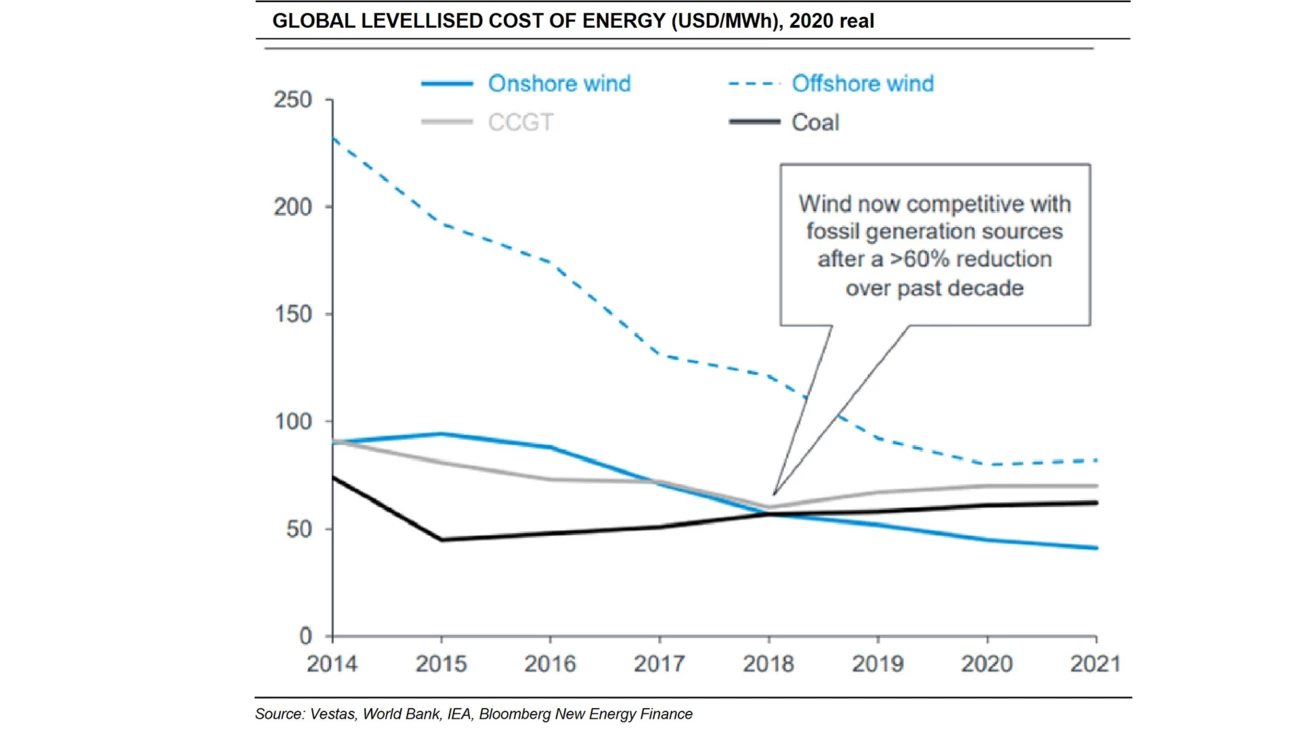

For wind power, a common and serious misunderstanding is to assume that it is subsidised today like it was in 2010. Vestas and indeed the whole industry ended up in financial turmoil in the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2009-10. At the time, probably over 95% of projects required subsidies to be financially viable, as the offtake was lower than the manufactured levellised cost of energy from the wind turbines. In the following decade, we reduced the levellised cost of energy by over 60%. This was driven by the size of the turbines, the efficiency of the technology, and arguably also improved connectivity and interaction with the grid, allowing better matching of wind energy production with current consumption in the grid.

Together with better operation and serviceability of the turbines, this has now given wind power the lowest levellised cost of energy. It beats nuclear power by a wide margin. Take the new Hinkley Point nuclear power station under construction in the UK. When it comes online, it will probably generate electricity at a cost of GBP 145 per MWh. The newest offshore wind farms in the UK run at some GBP 35 per MWh. And onshore wind farms in the UK run at perhaps GBP 15 per MWh. Offshore is still more expensive than onshore, because we have not yet solved the technology for floating platforms, but it will at some point in the coming decade converge to onshore cost levels. Construction at Hinkley Point has been ongoing for 20 years, and it is currently two and a half times over the original budget. This track record highlights that large-scale nuclear will be too slow and too costly for the energy transition we need to see in the next 30 years. At present, wind energy needs subsidies to be viable in less than 5% of the world markets. It is a far superior alternative.

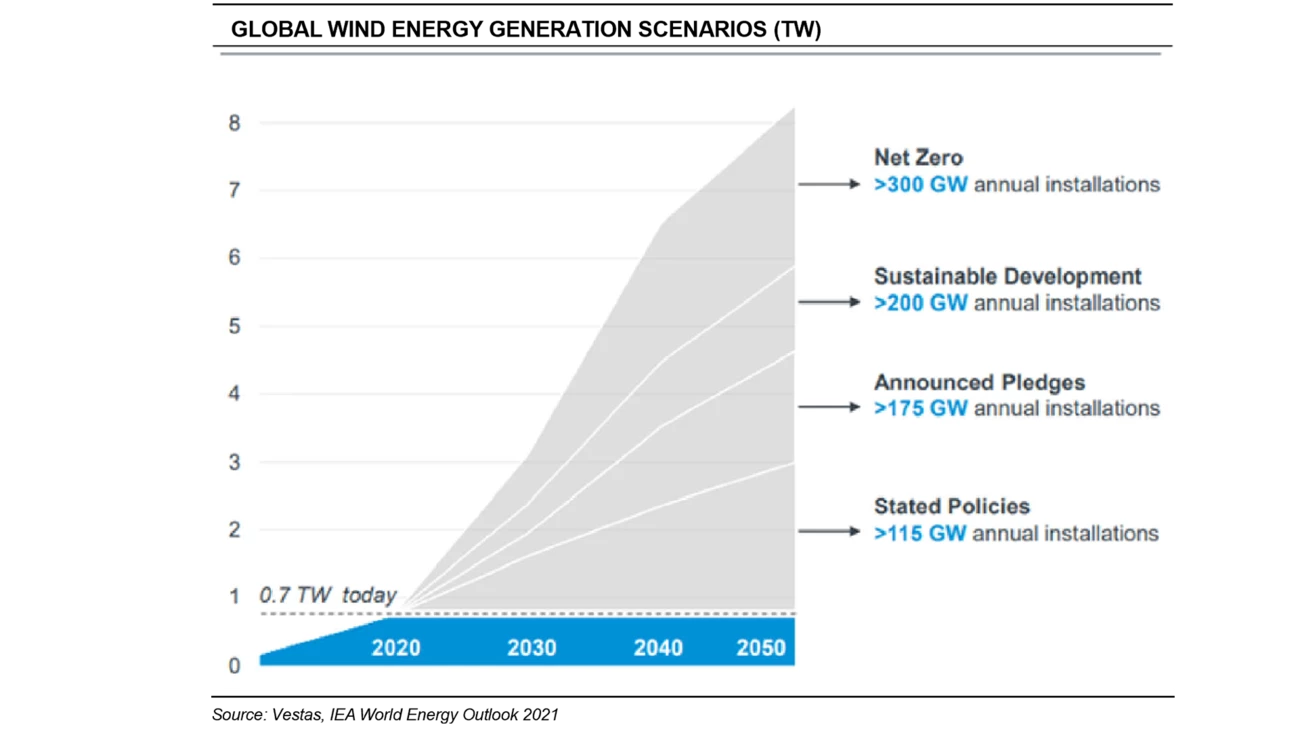

For governments today, there is no economic or sustainability-related reason not to invest in or promote wind power. The only obstacle is permitting for wind farms. As much as central governments encourage and plan for a rollout of more wind power, municipalities and local governments often try to block developments. And this is driving more interest in offshore wind farms, which constitute some 10% of the market today but will probably grow to more like 30% in the next decade. There is ample space in the ocean, and governments can tap into an additional revenue source by leasing out the seabed on which the wind farms are placed.

JT: How cost competitive is wind power compared with other energy sources today? How do you think this will evolve in the coming ten years?

HA: We will, of course, strive to continue to bring down the levellised cost of energy for wind turbines going forward. But it is important to highlight that we have reached a critical point now that wind power is, in fact, the lowest-cost energy source. We no longer need to push the technology to be economically viable without subsidies. We are there. The focus is shifting towards making wind power available in those parts of the global energy market where these renewable solutions are needed. Ten years ago, we needed a game change for the cost of wind energy. Today, we need optimisation and refinement.

A potential future new game changer for wind energy would be to increase its utilisation from 30% to perhaps twice that level, from being able to use the wind turbine in the grid or off the grid. This should come from the ability to store generated energy.