- Name:

- Susanne Spector

- Title:

- Head of Macro Research, Sweden

The labour market in Sweden has been more resilient than expected, but several signs now indicate that the situation will worsen. There is reason to believe that the deterioration of the labour market will be relatively mild, but a weaker labour market will heighten uncertainties.

In many countries, labour markets have been surprisingly strong over the past years. In Sweden, GDP stagnated last year, but employment still rose by nearly 3%. High demand and major labour shortages have opened doors for those who previously found it hard to enter the labour market. During the summer, the last milestone of the recovery was reached when the number of people unemployed for more than two years fell to lower levels than before the pandemic. According to statistics from the Swedish Public Employment Service, unemployment is at a 15-year low. Excluding persons in active labour market programmes, the unemployment level is the lowest in at least 30 years.

One reason why labour markets have performed better than expected may be the high inflation. Even though, for example, consumption is falling measured in constant prices, it is rising rapidly in current prices, which may contribute to maintaining company profits. Research on nominal effects is limited and so is past experience, but there may be reason to believe that strong nominal growth is important for the labour market in the short term.

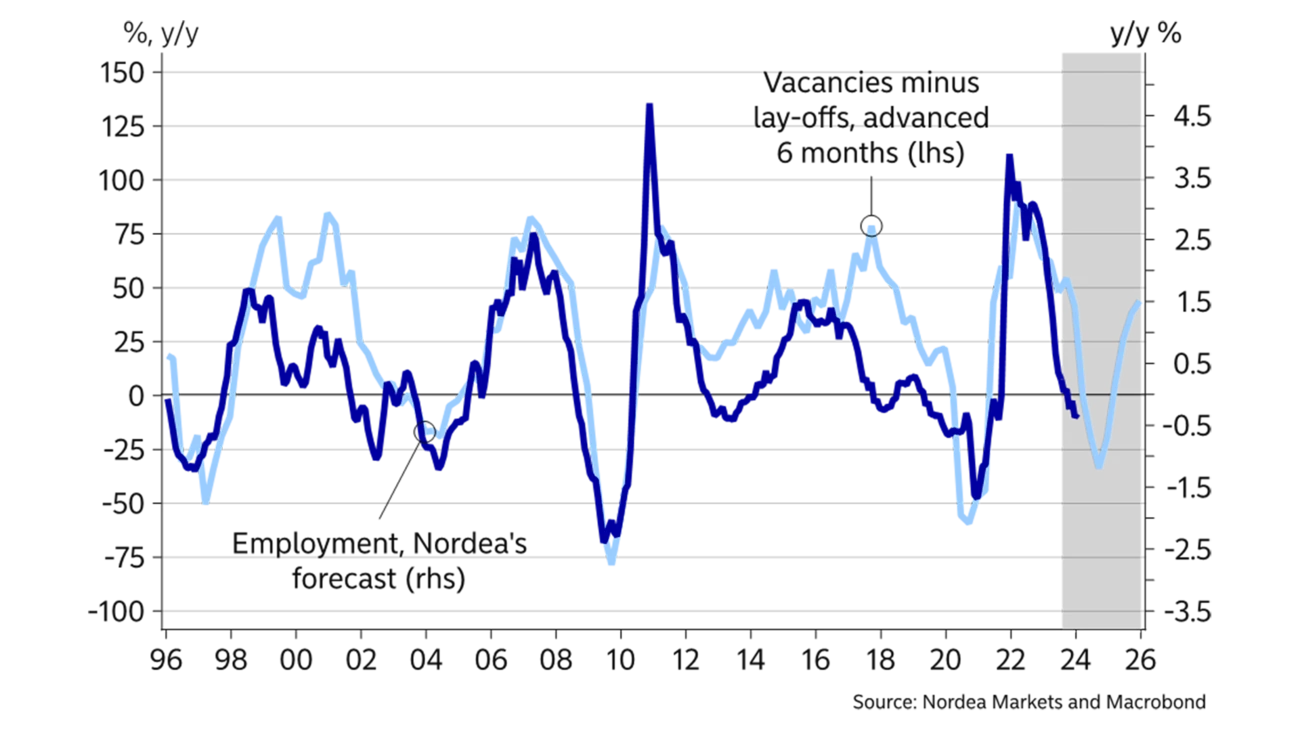

Now, however, there are clear signs that the labour market will slow down. The demand for labour is good, but the number of vacancies and companies’ recruitment plans have fallen from previous highs. In both the US and Sweden the demand for labour has declined, but unemployment has not risen so far, which fuels hopes for an economic soft landing. That is encouraging, but it is also worth noting that this is a relatively normal pattern at the beginning of a phase with a weaker labour market situation.

Employment and unemployment usually lag six months behind changes in new vacancies. For the demand for labour to keep falling without a deterioration of the labour market, labour market matching needs to improve considerably. The significant labour shortages could indicate that there is some room for improved matching when demand weakens, but it is probably not enough to avoid unemployment rising.

However, in the near term significant labour shortages may contribute to a slower reversal than usual as there are still vacancies to be filled and more companies than usual will likely choose to retain staff.

Now, there are clear signs that the labour market will slow down.

Another sign of lower demand for labour is the rising number of layoff notices. In July, around 3,500 persons were given notice, which is an unusually high number for that month. The number of layoff notices was exceptionally low last year, but has hovered around or just above its historical average throughout 2023. The influx of job seekers has also gone up. Moreover, the number of temporary staff and the number of hours worked have declined. All these variables are usually early indicators of a reversal.

The weekly statistics from the Swedish Public Employment Service also show a more pronounced deterioration of the labour market over the past weeks. According to data from the Swedish Public Employment Service, unemployment likely bottomed in July. Unemployment has already bottomed according to Statistics Sweden’s Labour Force Survey, but it is difficult to interpret Statistics Sweden’s data due to fewer respondents and the high volatility in the monthly figures. During the autumn, unemployment is expected to rise by around 0.5% point. Employment is also expected to slow and to start declining later in the autumn.

The decline in the labour market seems to be smaller than the decline in GDP and production. But a weaker labour market may emphasise the perception of a worsening economic situation. Resilience is decreasing and increasing unemployment weighs on disposable income, contributing to the general uncertainties that often characterise economic downturns.

This article originally appeared in the Nordea Economic Outlook: Not there yet, published on 6 September 2023. Read more from the latest Nordea Economic Outlook.

Sustainability

Amid geopolitical tensions and fractured global cooperation, Nordic companies are not retreating from their climate ambitions. Our Equities ESG Research team’s annual review shows stronger commitments and measurable progress on emissions reductions.

Read more

Sector insights

As Europe shifts towards strategic autonomy in critical resources, Nordic companies are uniquely positioned to lead. Learn how Nordic companies stand to gain in this new era of managed openness and resource security.

Read more

Open banking

The financial industry is right now in the middle of a paradigm shift as real-time payments become the norm rather than the exception. At the heart of this transformation are banking APIs (application programming interfaces) that enable instant, secure and programmable money movement.

Read more