The Covid-19 crisis has changed the inflation picture and the risks going forward. Inflation risks are now larger than disinflation risks for the first time in decades. There’s a considerable risk that inflation will stay elevated for longer than expected and break through to higher interest rates, even in Sweden where rates have long been low.

For companies with large balance sheets, the time to act is now to guard against the financial hit from higher interest rates, according to Nordea’s experts.

“You need to have the mindset of a risk manager, especially now,” says Nordea Chief Strategist Henrik Unell. “That doesn’t mean you need to hedge your entire balance sheet, but no hedging at all, given the current forces at play, would be very unwise.”

Low interest rates not a given

Unell emphasises that today’s low interest rates are not a given but rather a function of central bank activity.

“Even before the pandemic struck, we had an unsustainable long-term situation where central banks with their zero-rate policy and bond buying were eliminating risk premiums in the market,” says Unell.

Central banks argued that inflation was too low and the policies thus justified. However, by creating a bubble in government bonds, they inflated all asset markets, says Unell.

The situation worsened when Covid-19 struck, sending government debt skyrocketing as central banks’ balance sheets ballooned even further. In asset markets, rates continue to be low, credit spreads are tightening and stock markets are climbing, along with housing prices.

Covid-19 has changed the inflation picture

While the world economy’s low-inflation rut has lasted for decades, there are now inflation markers everywhere, including the goods sector and parts of the service sector. In addition, there’s a growing mismatch in the labour market, with employers reporting record-level difficulty filling vacant positions. That mismatch paves the way for wages to climb.

The central bank response is that the rise in inflation is only transitory and due to temporary factors such as higher energy prices and supply chain disruptions.

“We don’t argue with several of the factors being transitory, but we also believe there is a considerable risk that inflation will stay elevated for longer than the market expects,” says Unell. He adds that today’s yield curves don’t price in such a scenario.

Sweden vulnerable to rates picking up

Unell notes that no country has ridden the globalisation and disinflation train longer than Sweden.

“Our private debt levels are excessive and, more troubling, our mindset is that the Riksbank will never hike rates again,” he says. As a result, the balance sheet exposure to rates going up is “massive.”

For long rates in Sweden, it’s also important to focus on the international picture, according to Unell. The inflation forces at play, for example in the US, can easily travel through the system.

“Elevated inflation numbers in the US won’t go away in the short term. If they continue to be high, we’re going to have longer rates that climb from today’s low levels. That is at least certain,” he says.

Unell emphases that there’s still time for companies to buy insurance by hedging their exposure to variable interest rates, but it’s time to act.

Swedish real estate companies at risk

Stefan Juhlin, a director in Risk Solutions at Nordea Markets in Sweden, notes that Swedish real estate companies are especially vulnerable, given that a significant portion of their loan portfolios are often tied to floating interest rates.

He adds that many real estate companies operate under the mistaken assumption that inflation is not a problem for them because they have inflation-linked rental agreements. In other words, their rental income goes up each year in line with inflation.

“There’s a belief in the real estate sector that inflation is good for them, but it’s not,” says Juhlin.

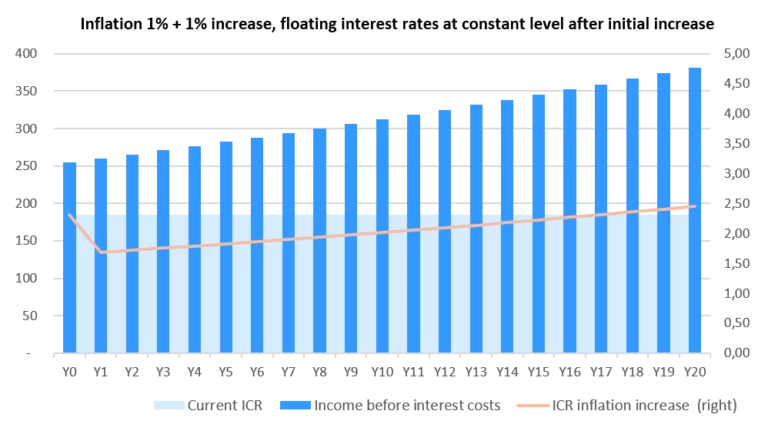

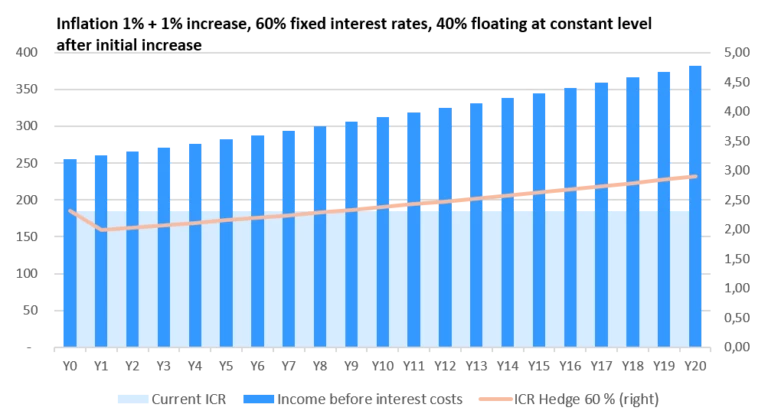

Should higher inflation break through to higher interest rates, the impact on interest costs is much faster than on the income side of the balance sheet.

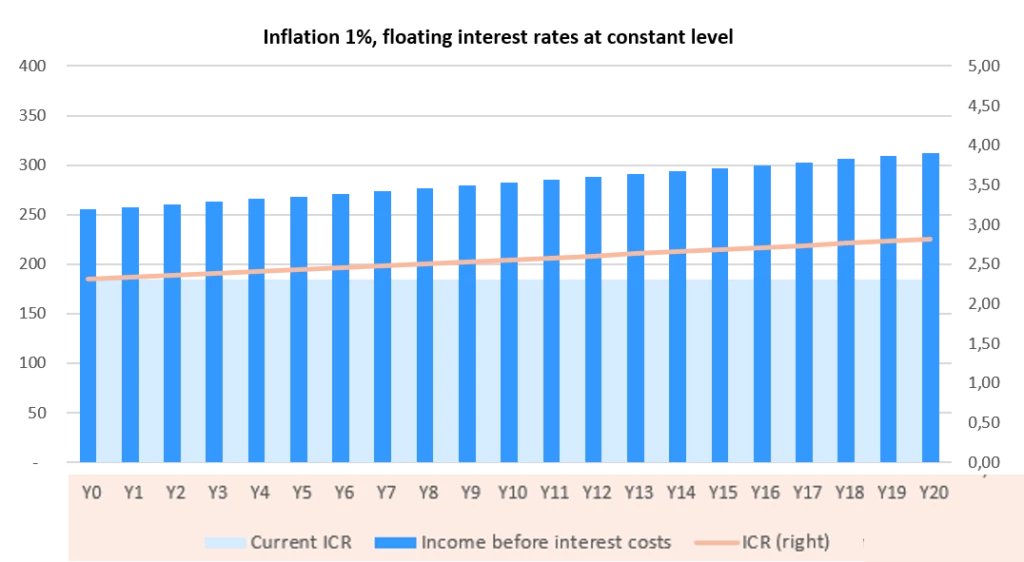

To illustrate the point, Juhlin highlights the effect higher rates have on the “interest-coverage ratio” (ICR) – the number of times a company can pay its interest costs with its income-before-interest-costs. An ICR of at least 2 is considered a minimum acceptable level, showing banks, credit agencies and bond holders that a company is in good financial health and able to meet its interest payment obligations.

The chart below shows a company with a current ICR of 2.3 (shaded blue region) and a 100% floating interest rate loan portfolio, assuming inflation of 1% and its floating interest rates at a constant level. Its income-before-interest-costs (the blue bars) will rise steadily due to the 1% inflation each year, as will its ICR.