Risks tilted towards higher interest rates

Central banks have no other option than to act forcefully against inflation, according to Unell, given their mandate of ensuring price stability. He explains that the disproportionate pandemic stimulus measures triggered inflation and the rise in interest rates. Deglobalisation and the war in Ukraine have added additional layers of complexity. There are currently no signs that inflation has started to fall, given the broad-based increase in prices of goods and services.

“I expect that Swedish inflation will not remain sticky at two-digit levels for too long but will eventually cool off in the near future,” he says. The real question is how quickly it will fall and where it will land, he adds. Unell argues that the inflation models central banks used in 2021-2022 were unreliable and gave a “false sense of security.”

Nordea’s forecast for the Swedish and global economies for 2023 is “quite gloomy,” Unell notes. Central banks are likely to adjust their monetary policy to adapt to the worse economic development in 2024, but that’s only if inflation falls to 2%. If price pressures persist, despite the weaker macroeconomic picture, interest rates will continue to stay elevated.

When it comes to interest rates, Unell sees the risks as asymmetrical – tilted towards higher rates rather than lower rates. He argues that the anatomy of markets has changed fundamentally and the low-rate paradigm is “dead and buried.” Even if the pace of inflation were to edge lower to 2%, that does not mean a return to the 0% interest rate environment.

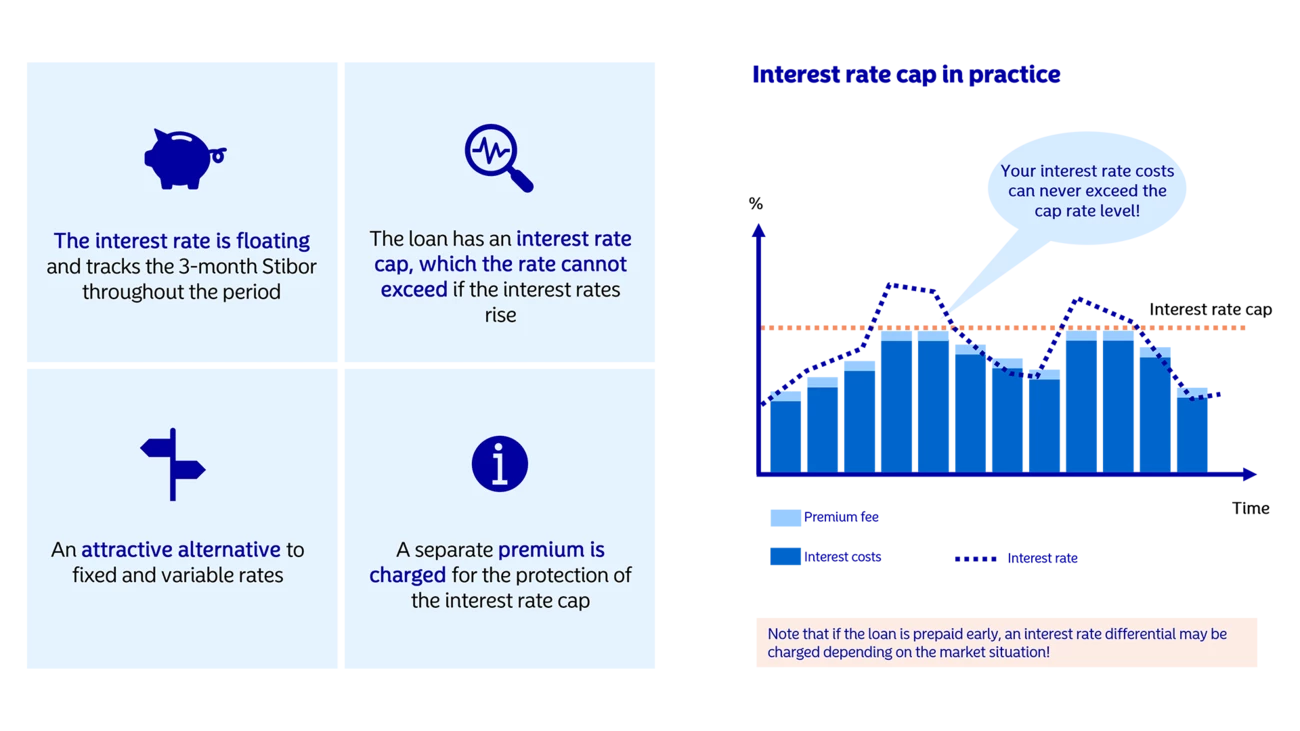

“Private individuals and businesses should realise that the current inflation and interest rate story has more than one chapter, and the future is highly uncertain,” he says. “Arguments such as ‘floating rate loans are always best’ sound pretty hollow to me.”