Fishing

The EU, Norway and the UK reached an agreement on fishing opportunities in the North Sea for 2025. This trilateral arrangement establishes total allowable catches (TAC) of over 958,000 tonnes, covering EU quotas of almost 463,000 tonnes for species such as cod, haddock, saithe, whiting, plaice and herring.

Additionally, the EU and Norway reconfirmed stable reciprocal access to North Sea waters, allowing both EU and Norwegian fishers to maintain key fishing activities. However, an agreement on access for blue whiting, Atlanto-Scandian herring and Atlantic mackerel was not reached, with consultations set to continue.

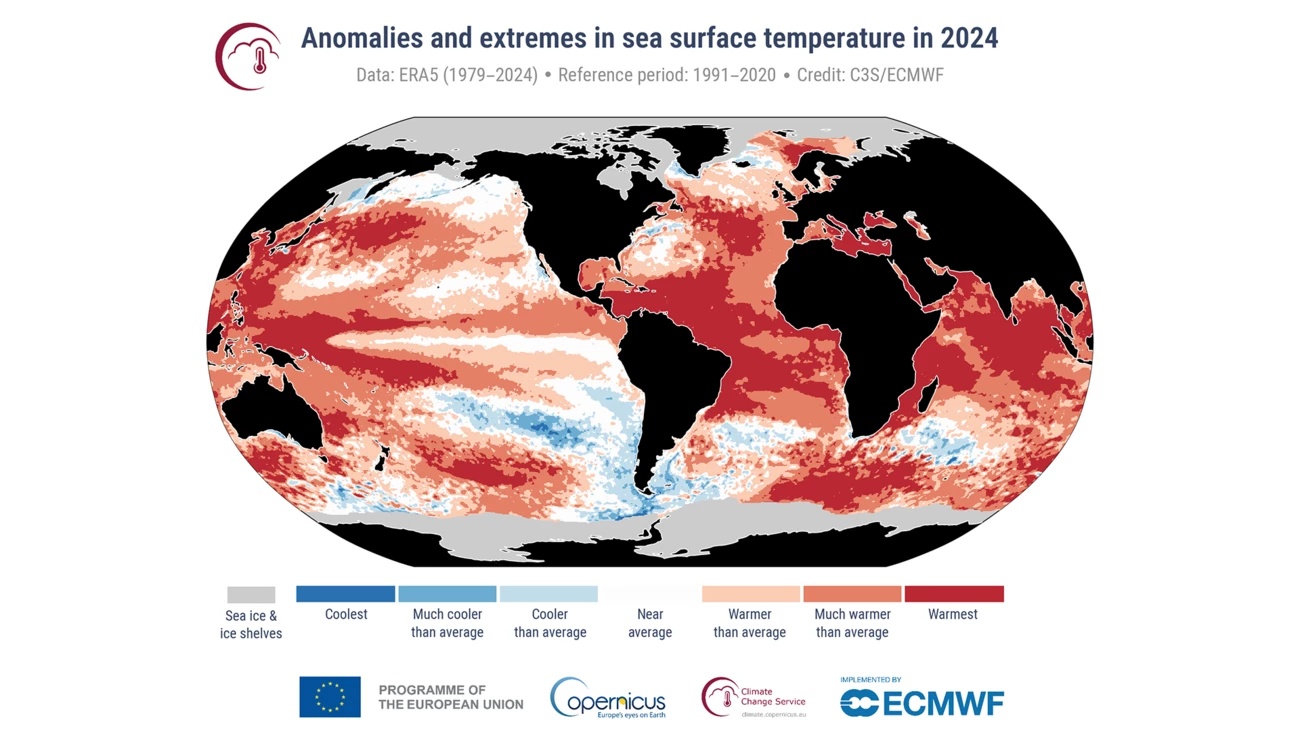

Despite the geopolitical tensions, Norway and Russia reached the 2025 fishery agreement in the Barents Sea. The quota for most species has been decreased since last year and in particular the quota for Atlantic cod is 25% lower, which is the lowest allocation since 1991. Most quotas decreased due to concerns about declining fish stocks, which depend on a combination of factors including climate and environmental issues (e.g. changes in sea temperature) and illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activities (IUU).

Transitioning to a more sustainable global food system

Fishing and aquaculture, while interconnected, present distinct risks and opportunities that can sometimes conflict. Declining wild fish catches, driven by depleting stocks and reduced total allowable catches (TAC), create opportunities for aquaculture to bridge supply gaps. However, the expansion of aquaculture can pose environmental risks, such as degradation of marine and freshwater ecosystems, which may further exacerbate the decline of wild fish populations.

Aquaculture and fishing are also closely linked through feed production. Carnivorous fish feed contains fishmeal and fish oils, which raises concerns over the increased pressure on wild fish stocks. However, improvements in feed conversion ratios (FCR), fish farm efficiency and extensive research into alternative feed, have alleviated pressure on wild fish. Nordic companies are actively exploring alternative feed sources to enhance self-sufficiency and reduce environmental footprints from feed ingredients. Innovations include the use of feed ingredients derived from insects, algae and novel sources like single-cell proteins (SCP).

Energy remained one of the major costs in the fishing fleet during 2023-2024. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions from vessels is central to the seafood industry, along with reducing emissions from feed production and distribution for farmed fish.

Prioritising sustainable practices and emissions reduction in both fisheries and aquaculture is critical to preserving marine ecosystems, supporting coastal communities and fostering the transition to a more resilient and sustainable global food system.

Nordea as a bank supports the fishing and aquaculture sectors in their climate transition by offering a range of different solutions and products to our large as well as small- and medium-sized customers.