- Name:

- Juho Kostiainen

- Title:

- Nordea Economist

Household purchasing power has weakened significantly over the past year. However, households have maintained their spending by tapping into their savings. The rise in interest rates is quickly translating into higher mortgage interest costs in Finland, although most mortgages have a repayment plan that decreases the amount of loan principal repaid when interest costs increase.

Household purchasing power has been tested over the past year, as inflation has accelerated and interest rates have shot up. Meanwhile, wages have risen moderately, despite the fact that the wage increases agreed for this year are higher than previously. The real wages of employees decreased by 6% over the past year.

Pensions and other benefits, which are mostly inflation-indexed, have risen at a higher rate than wages. In addition, higher employment has increased the total disposable income of households. Despite this, disposable income contracted in real terms by 4% in the Finnish economy as a whole last year.

Purchasing power began to deteriorate in the latter half of last year, causing private consumption to decline moderately. The consumption of goods, in particular, has decreased, and Nordea’s latest card transaction statistics foresee a slowdown during the spring in service consumption, which has so far held up well.

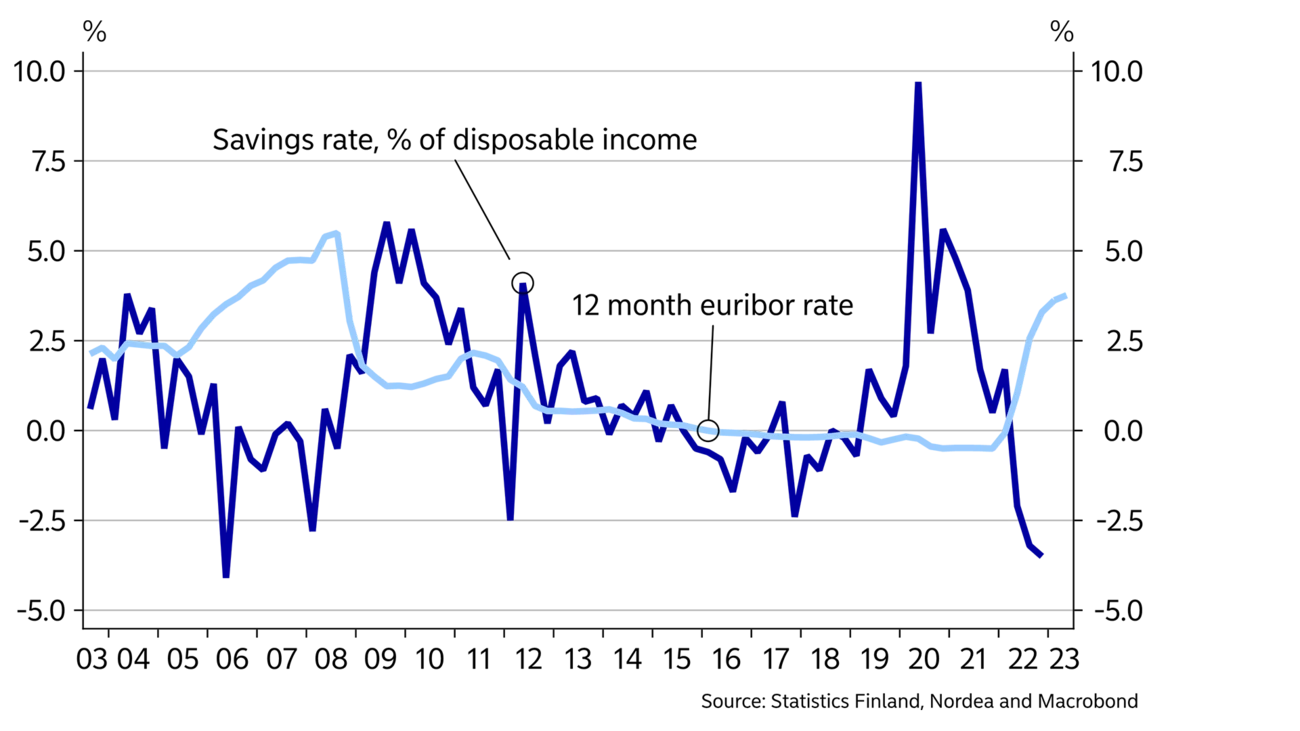

In real terms, consumption hasn’t decreased year-on-year as much as income. As a result the household savings ratio has fallen into negative territory because consumers have compensated for their weakened purchasing power by tapping into their savings to maintain their lifestyles. Over the past couple of years, households managed to accumulate a considerable amount of extra savings, ten billion euros in total, of which slightly more than seven billion euros were still intact at the end of last year.

The savings ratio typically falls when the future outlook for households improves, and it rises when economic uncertainty and the prospect of unemployment increase. With the employment level persistently high, the savings ratio has remained negative.

The savings ratio typically falls when interest rates rise.

Mortgage holders have been saddled with a particularly large increase in costs, as interest rates have risen by nearly four percentage points in one year. In Finland, 97% of mortgages are tied to short-term reference rates of 12 months or less. Around 25% of mortgages have an interest rate cap or similar hedge, but the majority of mortgage holders have already been hit with higher loan servicing costs as a result of the rise in interest rates.

The majority (76%) of new mortgages in Finland are annuity loans in which all future monthly payments increase by a similar amount when interest rates rise. This means that the repayment of loan principal is weighted towards the end of the loan period, when interest rates have a lesser impact because the amount of principal is lower. As a result, the monthly payment on an annuity loan doesn’t increase to the same extent as interest costs. Take, for example, a 20-year mortgage of 200,000 euros. If the interest rate increases by three percentage points, interest costs will increase by 500 euros per month but the monthly payment as whole increases by less than 300 euros.

Annuity loans and loans with fixed equal payments (11% of all mortgages) automatically lead to a decrease in how much borrowers save when interest rates rise, and thus push the household savings ratio down even if people don’t actively spend their savings. An increase of three percentage points in the average interest rate on all mortgages leads to a drop of about one percentage point in the household savings ratio.

Mortgage households have a higher income than average, and the largest mortgages in both absolute terms and relative to income are concentrated among high-income households. As a result, the rise in interest rates has hit high-income households the hardest, but these typically have more room to adapt their consumption or spend other savings to cover their interest costs. Low-income households, on the other hand, typically live in rented dwellings. Rents have risen very moderately, by about 2% annually, so the increased financing expenses have mostly been borne by landlords for the time being

This article originally appeared in the Nordea Economic Outlook: The Inflation Standoff, published on 9 May 2023. Read more from the latest Nordea Economic Outlook.

Corporate insights

Despite global uncertainties, Sweden’s robust economic fundamentals pave the way for an increase in corporate transaction activity in the second half of 2025. Nordea’s view is that interest rates are likely to remain low, and our experts accordingly expect a pickup in deals.

Read more

Economic Outlook

Finland’s economic growth has been delayed this year. Economic fundamentals have improved, as lower interest rates and lower inflation improve consumers’ purchasing power. However, the long period of weak confidence in the economy continues to weigh on consumption and investment.

Read more

Economic Outlook

The monetary policy tightening initiated by the ECB in 2022 halted economic growth in Finland and sent home prices tumbling. So why isn’t the monetary policy loosening that began a year ago having a positive effect on the Finnish economy yet?

Read more