- Name:

- Torbjörn Isaksson

- Title:

- Chief Analyst

Torbjörn Isaksson

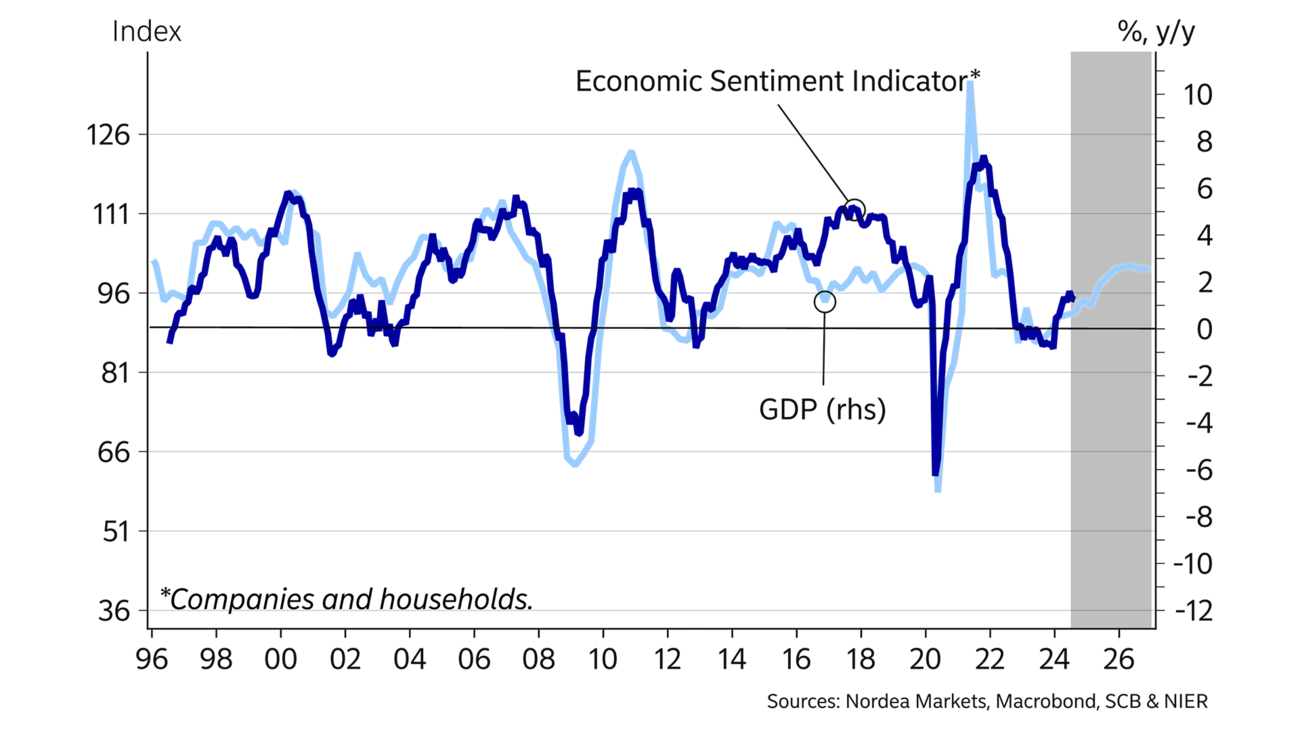

Households are still under pressure, due to the earlier uptick in inflation and higher interest rates. The situation is fragile, but with upcoming rate cuts, a significant decline in household consumption will be avoided. Demand is at its weakest now, and the domestic economy will gradually start to pick up in H2 2024. Exports are also improving, but the strength of the recovery is unusually difficult to estimate. Inflation will most likely remain below but close to the 2% target. The Riksbank's policy rate is significantly higher than before the pandemic, even at the end of the forecast period.

The multi-year economic stagnation in Sweden continued in H1 2024. Households' interest payments peaked at the beginning of the year, purchasing power was weak and unemployment rose.

The worst is over for households and conditions are in place for a recovery. Home prices started rising in the spring, when the Riksbank made the first rate cut. Household consumption will improve in H2 2024, while the demand for labour will be affected with a slight lag. Thus, unemployment should continue to climb in the near term, and the reversal in the labour market will not occur until year-end.

Despite rapid rate cuts in the near term, the Riksbank's policy rate should remain at a significantly higher level than before the pandemic. Large parts of the forecast period are thus characterised by a continued adjustment to a persistently higher interest rate level. This will slow the recovery and con-tribute to the gradual improvement of the Swedish economy and housing market.

Household consumption was remarkably weak until mid-2024. After the unusually sharp deterioration in 2023, household purchasing power slowly began to pick up in H1 2024, thanks to falling inflation and increased wages, and purchasing power will improve further ahead. Gradually lower interest rates should ease the burden on households with mortgages, whereas the incentive to save will start to decline. Although the amortisation requirement will likely be reduced, it will have no major impact; it will improve households' cash flow slightly though.

An important and positive factor is also that uncertainty about inflation and interest rates has de-creased. This should reduce household buffer savings, which have been high in recent years.

The recovery will gain momentum next year and in 2026. Pent-up demand is strengthening the upturn, while relatively high financing costs are pulling in the other direction. By mid-2025, mortgage rates and the interest rate ratio – interest expenses relative to disposable income – will still be twice as high as before the pandemic.

| 2023 | 2024E | 2025E | 2026E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Real GDP (calendar adjusted), % y/y | -0.1 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 2.6 |

Underlying prices (CPIF), % y/y | 6.0 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

Unemployment rate (LFS), % | 7.7 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 7.9 |

Current account balance, % of GDP | 6.1 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 3.2 |

General gov. budget balance, % of GDP | -0.6 | -1.9 | -1.7 | -0.3 |

General gov. gross debt, % of GDP | 31.6 | 34.0 | 35.3 | 35.4 |

Monetary policy rate (end of period) | 4.00 | 2.75 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

EUR/SEK (end of period) | 11.10 | 11.50 | 10.70 | 10.60 |

Mortgage rates are also central to the housing market. Home prices are expected to recover by 5-10% until the end of 2025. Residential construction should remain subdued. The gap between the costs of residential construction and households' financing options will narrow in the forecast period but only to a small extent.

Another reason for subdued residential construction is the sharply slowing population growth in recent years. According to Statistics Sweden's projection, the population will grow by about 25,000 people per year from 2024 to 2026. As the average household consists of two individuals, the demographic trend suggests a construction need of about 15,000 new homes per year compared to the peak year of 2021, with 70,000 housing starts. Domestic migration and demolition of homes suggest that the need is greater than the population growth indicates. We forecast at around 20,000 housing starts every year in the forecast period.

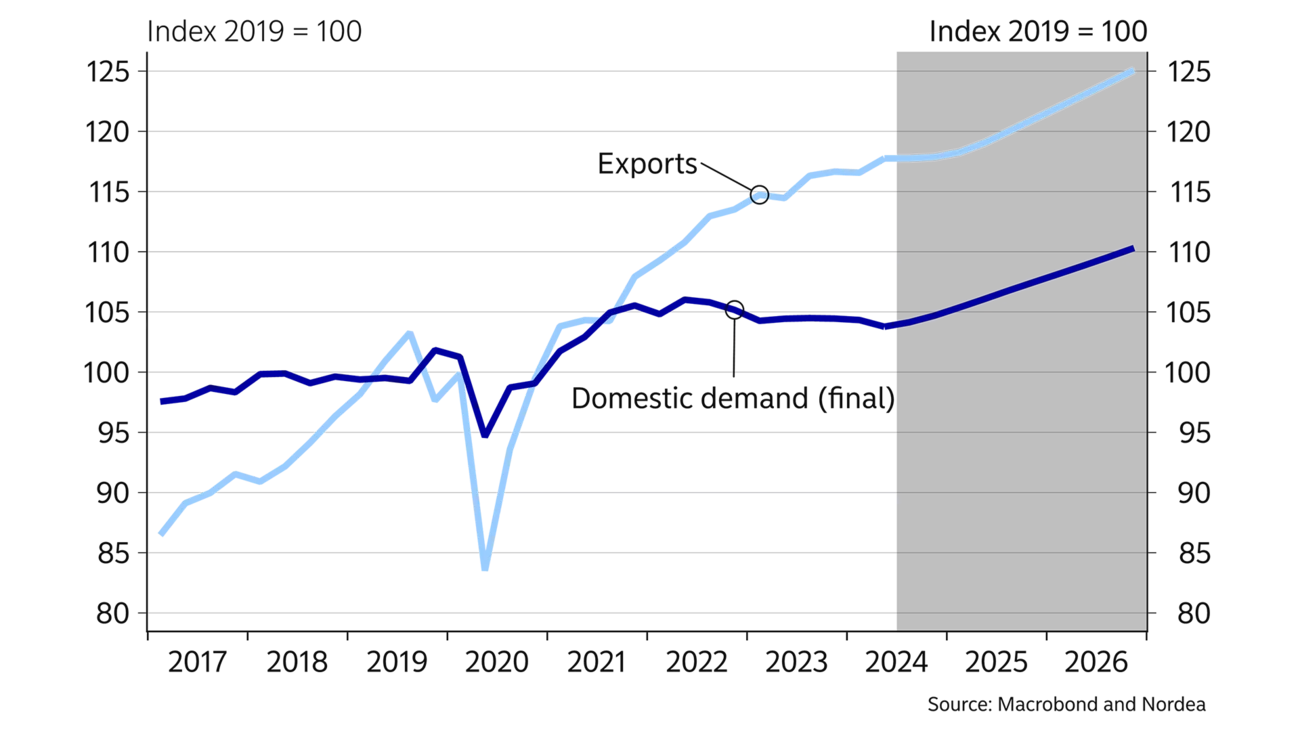

Other fixed investments develop much better. The private services sector has grown significantly in recent years; the surprisingly strong export of services is likely a contributing factor. Service sector investments will level out in the near term and then return to a rising trend. Industrial investments are also expected to have a temporary slowdown in the near term.

The low population growth reduces the need for new schools and kindergartens, dampening investments in the local government sector. On the other hand, there is a massive need for maintenance and replacement investments. In addition, defence spending is increasing, and, at the same time, the energy sector needs to be expanded. Consequently, consumption, as well as public investment, will increase at a steady pace in the forecast period as part of an expansionary fiscal policy. The budget deficit will increase to about 1% of GDP on average from 2024 to 2026. Public debt will go up but still be around 35% of GDP.

Large parts of the forecast period are characterised by continued adjustment to a persistently higher interest rate level.

Despite weak global trends, exports have risen much more than expected in recent years. Consequently, a substantial drop in GDP was avoided, although central parts of the Swedish economy have contracted.

The weak SEK exchange rate may have contributed to the strong export trend. The most tangible effect of a weak SEK on GDP is usually improved net tourism figures, as Swedes more frequently choose to stay at home while the influx of tourists increases.

The effect of a weak SEK on other export components is difficult to assess. This is probably positive but likely of a marginal nature. Instead, there seem to be favourable long-term trends. This especially applies to the export of services, which has sky-rocketed across the board – especially after the pandemic. However, the export of goods has also increased relatively fast in recent years, especially the export of vehicles, despite a generally subdued global demand.

The global economy is improving, and we thus expect exports to rise in the forecast period. Assessing global trends is very difficult. A further aggravating fact is that Swedish exports have deviated from international trends, with risks of a better/worse development of exports than assumed in the forecast.

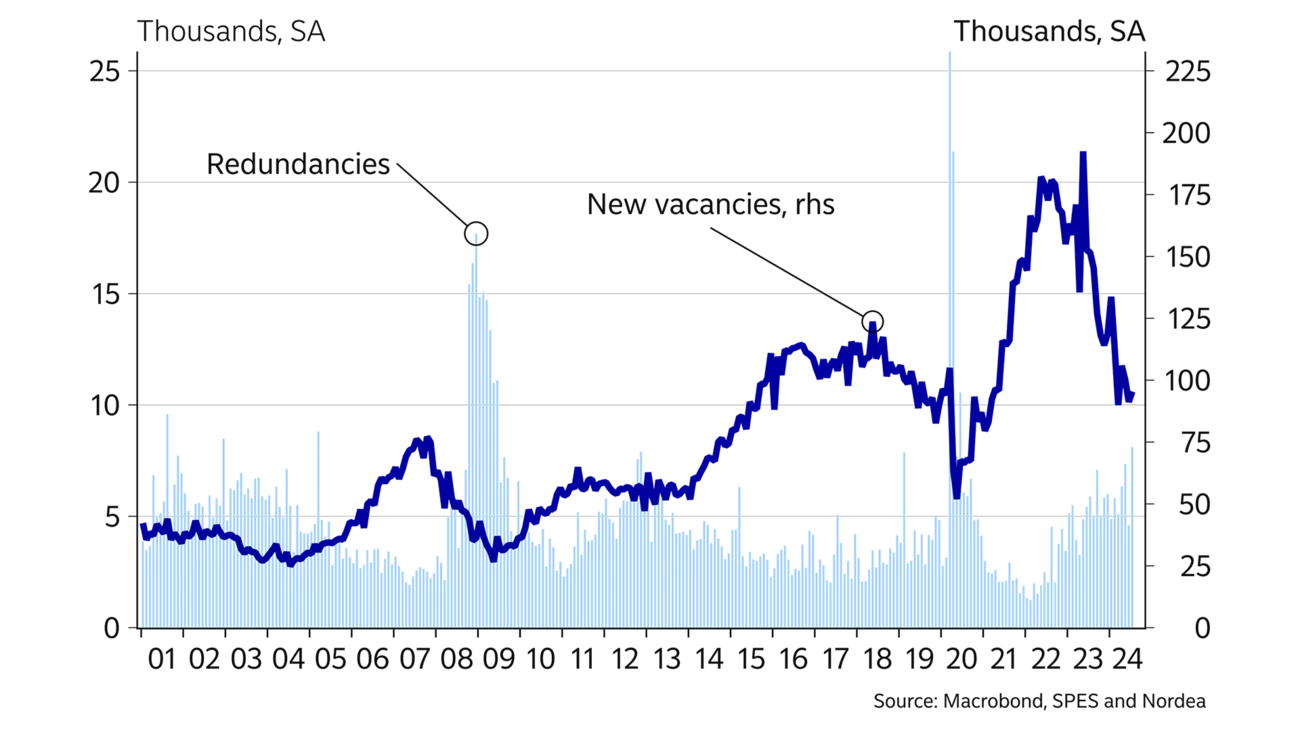

The stagnation of the Swedish economy affects the labour market. The number of new vacancies has halved since the peak in 2022, and the number of redundancies has continued to rise during the summer. After the unusually strong starting point, the demand and need for staff is now lower than normal, implying that unemployment will continue to rise.

The labour market situation will likely thus continue to deteriorate during the autumn. However, it should improve after the turn of the year, when the Riksbank's rate cuts have started to take effect, the Swedish economy is growing again and the demand for labour will rise. The fact that many companies have kept their employees over the past years, i.e. labour hoarding, will likely contribute to the labour market gradually recovering.

Wage growth picked up in early 2024 but has fallen back in line with agreements. Lower inflation and subdued demand for labour indicate continued low wage drift. The new wage agreements to be concluded in the spring of 2025 are expected to land in the same range as for this year, according to our forecast. This means that total wage growth will likely stabilise around 3.5% per year.

Wage growth in the coming years will likely be higher than the 2.5% or so in the 2010s but does not pose a threat to the inflation target. Overall, the inflation pressure is modest. In particular, a large supply of cheap goods seems to be in the world market, which should also benefit Swedish consumers. Moreover, energy prices have normalised.

Some previous cost increases are still spilling over into consumer prices though. For example, SEK deterioration in recent years still contributes to higher consumer prices, albeit modestly. Food inflation is also expected to go up somewhat in the near term. Rents for rental flats and fees for tenant-owned apartments will likely increase relatively sharply in 2025 as well. In conclusion, inflation is estimated to be below but not too far from the inflation target in the forecast period.

Therefore, the Riksbank has no domestic reasons to keep the policy rate at tightening levels. When inflation is low, the too weak Swedish economy will likely be more important in terms of monetary policy decisions. Moreover, with lower global interest rates, the depreciation pressure on the SEK will most likely ease. We thus expect a series of rate cuts in the near term.

In the long term, we estimate that the Riksbank's policy rate will fluctuate around 3%, which we consider a neutral and normal policy rate level. During the 2010s, the central banks' biggest concern was that price growth and inflation expectations were too low. These problems have been eliminated, owing to a surge in inflation in recent years. Instead, the Riksbank and other central banks will probably react faster to any indications of a pickup in inflation. This also suggests the policy rate will be higher in the coming years than before the pandemic.

However, based on the rapid debt increase during the past 20 years, especially in the household sector, a policy rate of 3% will likely have a tightening effect in the short term. The weak economic cycle motivates a lower policy rate than normal. Overall, we estimate the policy rate will bottom at 2% in the forecast period.

In the long run, the Riksbank's policy rate should fluctuate around 3%.

The SEK trade-weighted exchange rate has been volatile over the past year. Most recently, the exchange rate seems to have firmed though. Swedish GDP growth has lagged in recent years, but the high interest rate sensitivity means that growth may be in line with or better than that of other countries when interest rates are cut. Moreover, structural strengths will likely support the SEK, for example a competitive business sector and low public debt. We thus expect the SEK to strengthen somewhat during the coming year. The SEK exchange rate has an impact on inflation, and, if the SEK appreciates faster than expected, inflation may be lower than our forecast.

This article first appeared in the Nordea Economic Outlook: Precision Play, published on 4 September 2024. Read more from the latest Nordea Economic Outlook.

Sustainability

Amid geopolitical tensions and fractured global cooperation, Nordic companies are not retreating from their climate ambitions. Our Equities ESG Research team’s annual review shows stronger commitments and measurable progress on emissions reductions.

Read more

Sector insights

As Europe shifts towards strategic autonomy in critical resources, Nordic companies are uniquely positioned to lead. Learn how Nordic companies stand to gain in this new era of managed openness and resource security.

Read more

Open banking

The financial industry is right now in the middle of a paradigm shift as real-time payments become the norm rather than the exception. At the heart of this transformation are banking APIs (application programming interfaces) that enable instant, secure and programmable money movement.

Read more