- Name:

- Torbjörn Isaksson

- Title:

- Chief Analyst

After several turbulent years the pieces of the puzzle are gradually falling into place for the Swedish economy. Households’ consumption pattern normalises, export companies’ production will balance with demand and inflation will stabilise at low levels. Unemployment will go up, but several rate cuts from the Riksbank will pave the way for a gradual recovery. The recession will remain relatively mild.

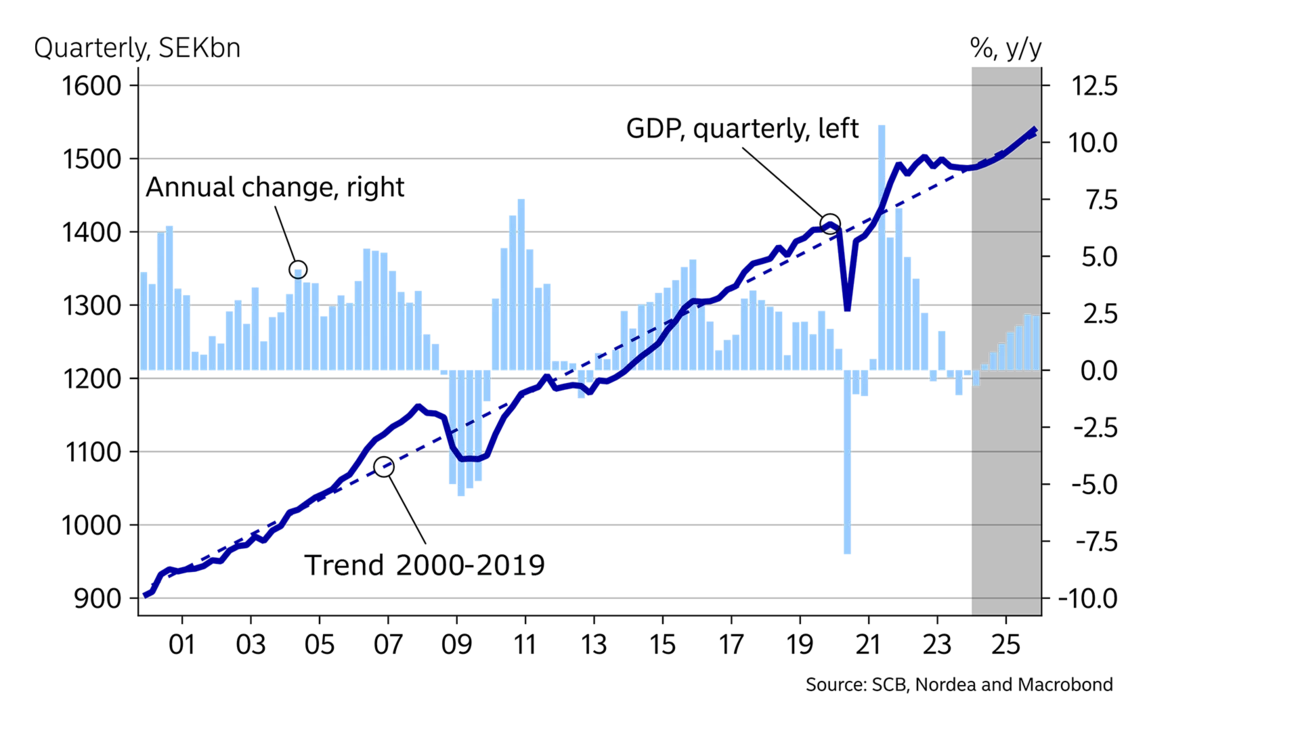

The Swedish economy has stagnated during the past two years. However, the economy has slowed from a very strong starting point, implying that resource utilisation is currently only slightly lower than usual.

The picture is mixed. Monetary policy tightening has had an effect, and sectors directly dependent on household demand have been affected by a sharp decline over the past two years. Other parts of the Swedish economy, especially exports, have performed better. This explains why GDP did not fall much last year even though key components of domestic demand saw the sharpest declines since early 1990s, except for the temporary drop during the pandemic.

Especially household consumption will start to increase in the first half of this year. An important driver is Riksbank rate cuts. Rate cuts are a welcome relief for many indebted households. However, the interest rate level will remain significantly higher than before the pandemic. Ongoing adjustment to higher interest levels thus characterises the forecast years and contributes to a slow recovery.

Monetary policy is key for the growth outlook and thus also a risk to the forecast. If rate cuts are postponed, households and companies will face increasing challenges. In such a scenario, GDP growth will be weaker and unemployment higher. However, more rate cuts and underestimated household resilience will lead to a faster recovery.

Households are consolidating. The debt ratio – debt relative to disposable income – peaked at 199% at end-2021 and has dropped 13 percentage points since then. The decline is explained by the rapid increase in household nominal income. However, debt has not gone down. Credit growth has halted, but households have not reduced their debts. This process will largely take place in the forecast period, and the debt ratio will fall to around 175% by end-2025.

The development is difficult to measure. In spite of the Riksbank’s easing measures, interest rates are expected to remain at a higher level than before the pandemic. If households want lower interest expenses, debt should be reduced. If so, there will be less room for consumption and home purchases. On the other hand, better than expected income trends could accelerate the consolidation process and increase the room for spending. Income has risen surprisingly fast in recent years and may continue to rise swiftly going forward.

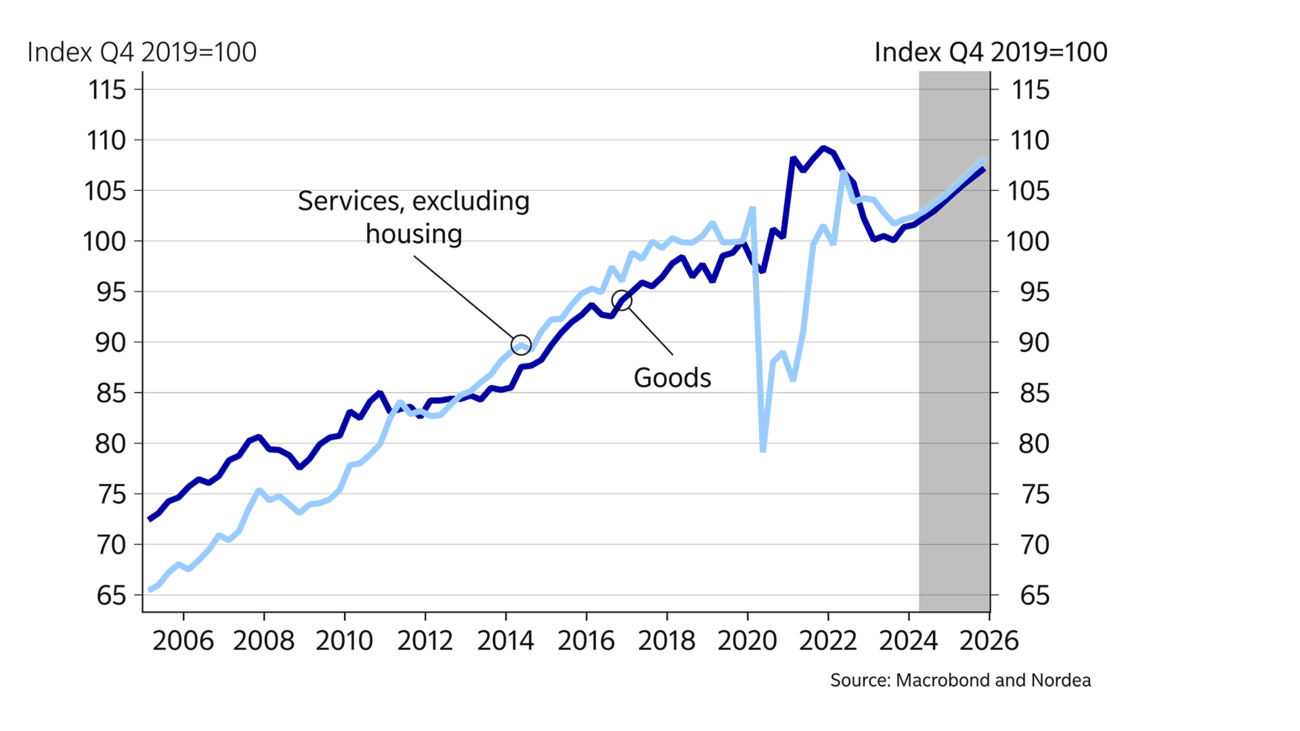

Low inflation and thus increasing purchasing power will support consumption trends, while the weaker labour market will create uncertainty and curb consumers’ propensity to spend near term. Overall, household demand will pick up in the forecast period, but relatively slowly and from a low level. Importantly, the consumption pattern will normalise after recent years’ extreme movements in the demand for goods and services. This will in turn, among other things, help to stabilise inflation.

Housing prices will have a similar development as consumption. Prices are expected to pick up as from Q2 this year, and will rise by 6% to year-end 2025. At end-2025 housing prices will still be 8% below the early 2022 peak.

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024E | 2025E | |

| Real GDP (calendar adjusted), % y/y | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| Underlying prices (CPIF), % y/y | 7.7 | 6.0 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| Unemployment rate (LFS), % | 7.5 | 7.7 | 8.4 | 8.2 |

| Current account balance, % of GDP | 5.6 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 5.6 |

| General gov. budget balance, % of GDP | 1.2 | -0.6 | -1.3 | -0.7 |

| General gov. gross debt, % of GDP | 33.2 | 31.2 | 32.8 | 33.5 |

| Monetary policy rate (end of period) | 2.50 | 4.00 | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| EUR/SEK (end of period) | 11.12 | 11.10 | 11.30 | 10.70 |

Investments are dominated by the sharp decline in residential construction. Last year’s drop in new housing starts lowered total investment growth by 4 percentage points and GDP by 1 percentage point. Residential construction will remain subdued in the coming years, according to our forecast. Last year, the construction of 29,000 new homes was initiated, and this year and the next the construction of new homes is expected to total around 20,000 per year. This is 70% fewer homes than the record year of 2021 with nearly 70,000 housing starts.

There are several reasons why housing construction is relatively low in the forecast period. The chief reason is the low population growth, which reduces the need for new homes, see the theme article Population shift. Other reasons are the high costs related to housing construction and households’ relatively high financing costs.

Last year, investment rose in other parts of the economy. For example, the manufacturing industry expanded, with the likely contribution from the green transition in the north of Sweden. Also energy investments rose. In addition, the important private service sector expanded, although moderately. Indicators point to a generally subdued trend, and investments will fall somewhat in the total business sector this year, according to our forecast.

So far the previously high inflation has to some extent restricted fiscal policy. The measures in the spring budget are, however, expansive. Together with already adopted measures, the unfunded reforms total SEK 60bn this year, corresponding to 1% of GDP. Next year fiscal policy measures of the same magnitude are expected. Households will get some tax relief, while large amounts will be allocated to healthcare, schools and other public services. A sizeable share will cover increased costs in the public sector in the wake of the previously high inflation. This capital injection will prevent staff cuts in the public sector rather than lead to more new hires or an acceleration of growth.

Rate cuts are an important factor for the recovery.

Exports beat weak global trends last year and rose by 3.3%. Once again services exports accounted for an impressive and broadly-based increase. By year-end services exports were an impressive 30% higher than before the pandemic and now account for 17% of GDP and nearly one third of exports. Services exports seem to be affected by global demand fluctuations with a relatively large lag. Last year’s downturn in world trade is thus expected to result in a temporary decline this year.

Also goods exports rose last year. The explanation seems to be that booming order books were thinning, for example, in the transport equipment industry. Order books are now balancing and more in line with the subdued global demand. At the same time global demand for goods looks set to recover after the very sharp decline over the past year. Thus an harmonisation is expected this year when goods exports will fall from a high level while global demand increases.

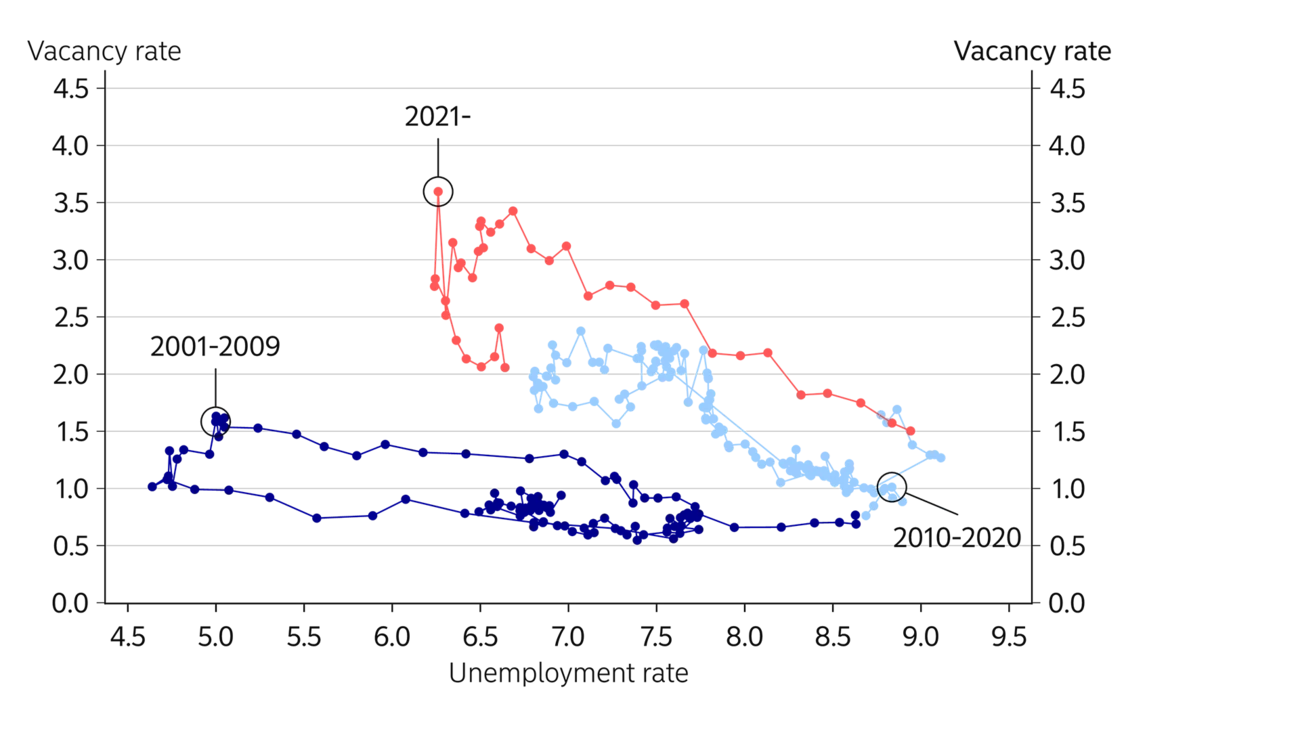

Simply put, labour demand can be split into the number of people employed and the number of vacancies. So far the decline in demand has mostly affected the latter, implying that the number of vacancies has fallen significantly more than employment has declined or unemployment has risen.

Another way of describing this development is by using the so-called Beveridge curve, see chart A. The Beveridge curve shows the correlation between the number of vacancies and unemployment. The curve often moves diagonally as there are few vacancies in difficult times and many unemployed people, while there are many vacancies in good times, and few unemployed people. In the years after the pandemic, the demand for labour was record high and labour shortage was significant. Since then the share of vacancies has declined without any large uptick in unemployment, which is unusual. But now we have reached the point where the Beveridge curve has started to move diagonally again and where changes in the demand for labour will have a greater impact on unemployment.

Indicators support the picture of a gradual labour market deterioration. The number of vacancies has nearly halved, but is still in line with pre-pandemic levels, and companies’ hiring plans are at decent levels. We expect unemployment to rise to around 8.5% later this year, which is around 1.5 percentage points up on the summer of 2022.

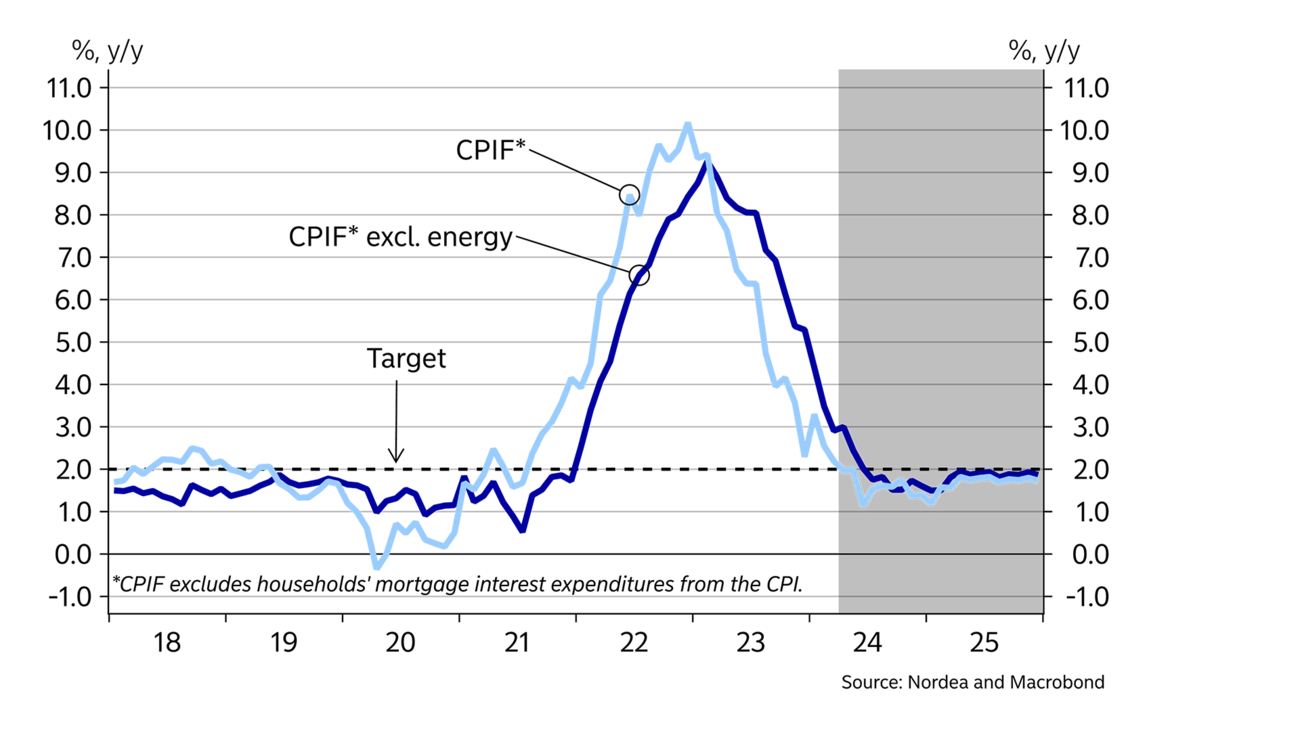

Since early 2024, wages have increased to just above 4% which is in line with last spring’s pay deals. From and including April this year, the second year of the pay deals starts with an agreed 3.3% increase. When new pay deals are concluded in the spring of 2025, they are expected to land roughly within the same range. Overall, pay deals will thus stabilise around 3.5% per year over time.

We have reached the point where low demand for labour will impact unemployment to a greater extent.

Wage increases at these levels are around 1 percentage point higher than before the pandemic, but still consistent with the inflation target. All in all, there are few domestic factors that could drive inflation to undesirably high levels. Moreover, outside Sweden there is an excess supply of cheap goods this year. Inflation will thus continue to fall and settle below the target from and including this summer, which will lead to a series of rate cuts from the Riksbank and a policy rate of 2.5% in December this year. As growth will recover in Sweden and the rest of the world next year and global cost pressures will increase somewhat again, inflation will stabilise near the inflation target, and the policy rate will remain unchanged.

The main risks of a higher policy rate than forecast exist by way of the SEK exchange rate. If the ECB only cut rates a few times this year, the Riksbank may decide to take a wait-and-see stance to avoid potential SEK weakening, which in turn could increase inflation. The concerning geopolitical situation likely poses the highest risk for the SEK. If the situation deteriorates, financial market uncertainty will likely increase, which may lead to a depreciation of the SEK. However, our baseline scenario is that the SEK will trade at relatively weak but stable levels against the EUR and USD near term, which will not prevent the Riksbank from cutting rates. Going forward, the SEK will strengthen somewhat as the Swedish economy’s strong fundamentals in the form of competitive businesses and solid public finances will feed through.

This article first appeared in the Nordea Economic Outlook: Falling into place, published on 24 April 2024. Read more from the latest Nordea Economic Outlook.

Sustainability

Amid geopolitical tensions and fractured global cooperation, Nordic companies are not retreating from their climate ambitions. Our Equities ESG Research team’s annual review shows stronger commitments and measurable progress on emissions reductions.

Read more

Sector insights

As Europe shifts towards strategic autonomy in critical resources, Nordic companies are uniquely positioned to lead. Learn how Nordic companies stand to gain in this new era of managed openness and resource security.

Read more

Open banking

The financial industry is right now in the middle of a paradigm shift as real-time payments become the norm rather than the exception. At the heart of this transformation are banking APIs (application programming interfaces) that enable instant, secure and programmable money movement.

Read more