JT: Do you see any differences in how you exercise your influence as an owner, compared with, for example, private institutional owners? More or less formal engagement? More or less hands-on? How active is your ownership?

AM: Every owner, of course, has their own individual approach, but I think that on a general level differences in how we operate compared with other major owners are only minor. We have been in continuous dialogue with Industrivärden, co-owners with us in SSAB, and with the Swedish Wallenberg family's FAM, co-owners in Stora Enso, as well as with other family and institutional owners in Finland. We work in very similar ways.

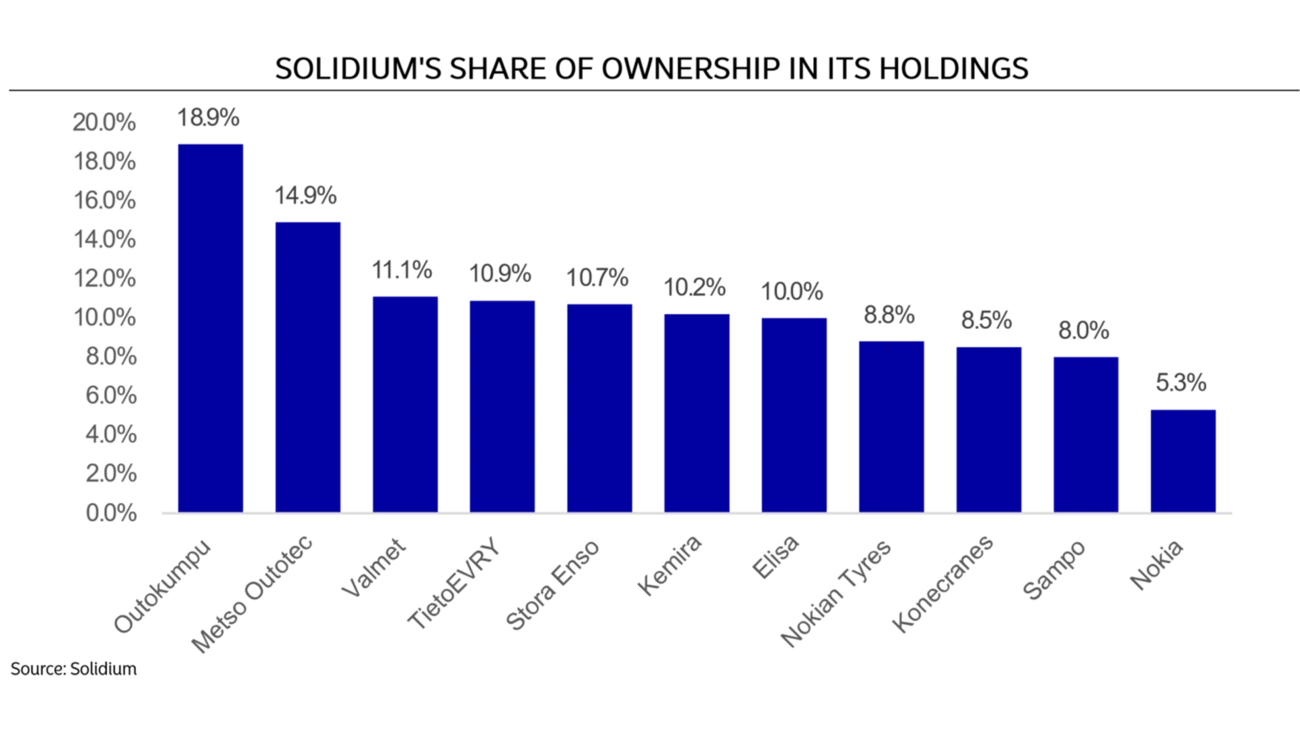

One difference with Solidium being state-owned is that we are not particularly tax-driven. We do not need to be concerned with owning at least 10% of a company in order be exempt from tax on dividends received. Another difference is that many other private major owners have an explicit ambition to be the biggest owner or to have a decisive influence.

We are very clear that we are open to co-operating with other major shareholders, and we don't strive for control of companies we invest in per se. Some big owners typically aim for a more dominant ownership level of some 20%, and to appoint the chairman and maybe one other board member. With our investment team of seven people, it would not be reasonable for us to aim for such an active and ambitious level of control in the companies we invest in. So far, we have not considered ourselves to have the staffing or all the competencies to exercise ownership influence on such a basis.

Day-to-day, we work in similar ways to our peer owners, analysing the companies and their competitors and industries, and meeting with the companies at the CFO, CEO, Head of Sustainability and chairman level. When I joined Solidium, we did not have any board representation in our portfolio companies. We decided to seek this, and allow for it to take time in order to find the right candidates for the boards. Being state-owned, we don't run any friends-and-family networks as some of our private peers do. We only nominate board members who are employed by Solidium or are members of Solidium's board, which means we have a limited pool of candidates for board representation.

I would say we are broadly similar to other major owners in our governance approach, but we are more active as an owner, not least through our gradually increasing board representation, than a typical institutional investor.

JT: Is your agenda as an owner affected by the fact that you are representing the state? Additional non-financial targets or objectives? Level of ambition for sustainability?

AM: It is explicitly stated in Solidium's mandate that we do not have any political objectives or agenda. There is no other mission for us than working for our portfolio companies to perform well. At the beginning of our current mission, I think Solidium was a pioneer in championing sustainability issues, as our owner considered it a priority. But I would say that over the years, other institutional owners have caught up and now consider it similarly important. Differences in attitudes towards sustainability have narrowed, particularly in the past three to four years.