- Name:

- Samuel Pendergraph

- Title:

- Senior ESG Analyst

Siden findes desværre ikke på dansk

Bliv på siden | Fortsæt til en relateret side på danskAs Europe’s plastics industry faces declining production and recycling challenges, retailers grapple with supply chain shifts that may impact climate goals. Find out how changing manufacturing patterns and global competition are influencing the environmental landscape, and what it means for the retail sector’s sustainability efforts.

Plastics are extensively used across many industries, particularly in retail and wholesale trade. These sectors depend heavily on plastics for both products and packaging, which leads to significant plastic consumption and waste. In the retail sector, the majority of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions fall under Scope 3, originating from purchased goods and services. These can account for over 80% of a company's GHG emissions.

Reducing emissions in this category is challenging, as it can conflict with business growth objectives. Increasing business without altering a product's carbon intensity will inevitably raise GHG emissions. Retailers must be diligent in their product procurement.

One effective strategy for maintaining lower product carbon intensity is to purchase locally within the continent. However, this option is becoming less viable for essential materials like plastic, given the decline in European manufacturing.

Recently there have been chemical manufacturing facility closures within the EU, including Exxon in France and Sabic in the Netherlands. Some of these shuttered plants were key providers of the feedstock chemicals needed to produce materials such as plastics. This trend is not a new; the chemical industries have been in structural decline for years due to competition abroad (primarily Asia) and increased energy costs within Europe.

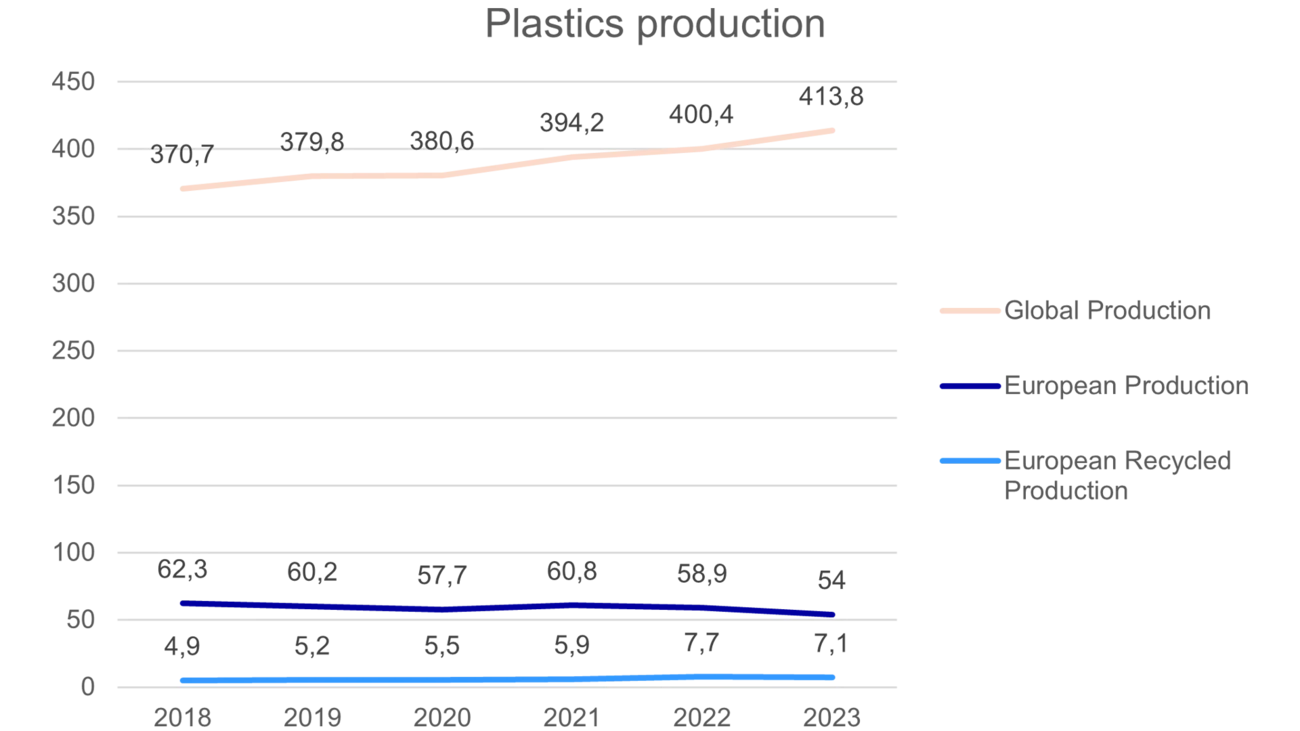

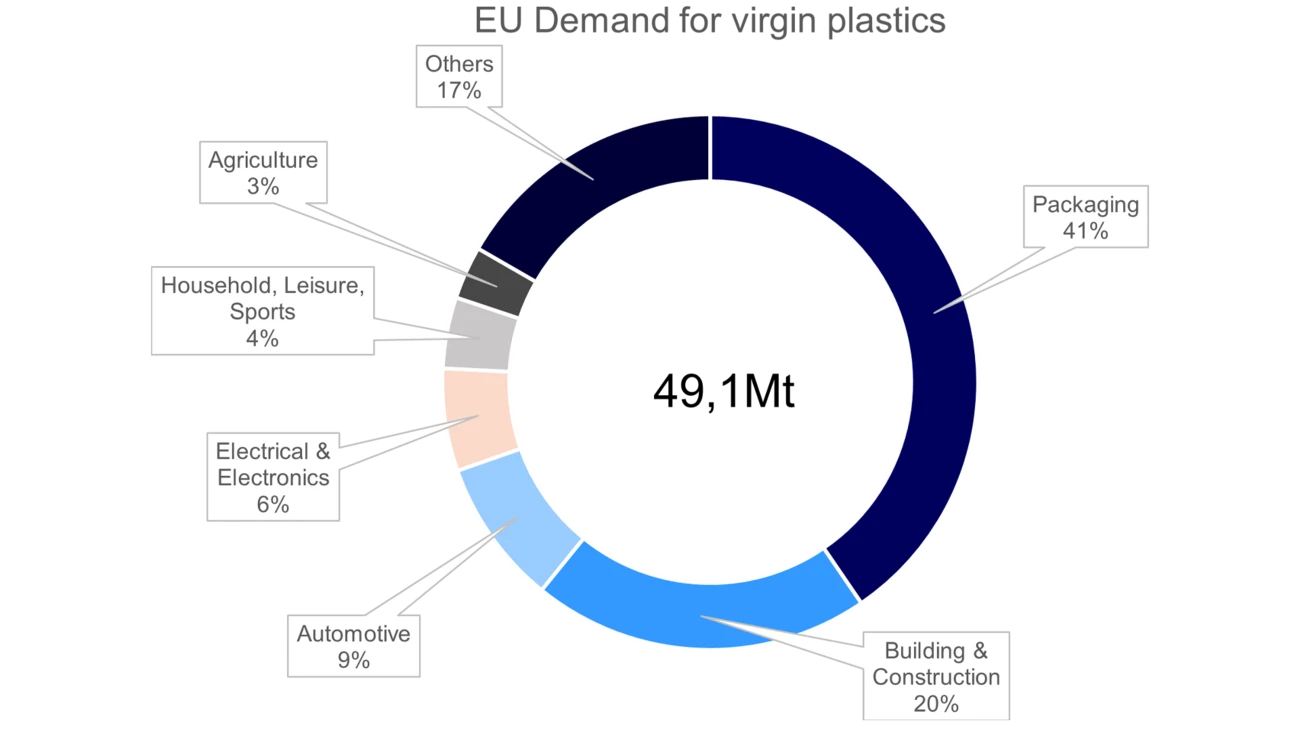

From 2019-2023, European plastics production decreased by 10%, while global production increased by 9% during that same period. The largest European demand driver for virgin plastics is packaging, accounting for 41% of usage. Packaging is a significant driver for material consumption and, by extension, a major contributor to purchased goods’ Scope 3 emissions.

While plastic recycling has increased over this period, it has recently plateaued and even slightly declined year-over-year, resulting in a deficit that has led to increased sourcing of virgin plastics. Notably, in 2022 over 19% of packaging waste generated by the EU, equivalent to 16.1 million metric tons, was plastic.

More recently the European Recycling Industries (EuRIC) wrote a brief yet poignant letter warning that European recycling is at a “breaking point.” They emphasised that urgent action is required to avoid significant setbacks in achieving climate and circularity goals.

McKinsey recently outlined the major drivers for decarbonising the plastics value chain. Two primary drivers they identified are energy efficiency improvements and the energy mix of the electrical grid. In one example, they demonstrated that the electrical grid’s composition can result in polyethylene manufactured in China having 5-22% higher emissions compared to Europe. Other estimates suggest that polyethylene and polypropylene production in China can have over 60% greater in carbon intensity than in Europe.

This discrepancy is even more pronounced for polycarbonates, which are used in more durable goods and can have more than double the carbon footprint when produced in China compared to Europe. At a country level, Chinese electricity emission factors are almost 2.5 times greater than those of OECD European countries, according to the IEA and Nordea's analysis.

Shifting more plastics production to China will inevitably raise the carbon intensity of key plastics like polyethylene and polypropylene due to the electricity demands of producing the monomers and subsequently plastic resins. Processed plastics, which are imported from China in greater relative quantities compared to plastic resins, require even more electricity usage and will likely further increase the carbon intensity compared to European manufacturing.

Despite electricity being within the scope of products covered by the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), polymers are not included. This lack of coverage means there is no framework to compensate for the higher emissions created by more carbon-intensive electricity used in polymer production outside the EU.

There is no framework to compensate for the higher emissions created by more carbon-intensive electricity used in polymer production outside the EU.

In our previous retail and materials article, we discussed how compliance with various chemicals regulations is challenged when materials are sourced outside the EU. Beyond the environmental concerns, the loss of industrial production has profound implications for local communities that depend on these industries for employment.

As of 2023, the European plastics industry employed over 1.5 million people, according to the Society of Plastics Engineers (SPE). The acute impact of industry decline will reverberate well beyond environmental issues.

The EU and its member nations should consider evaluating their current industries, particularly those that are electrically intensive, and consider climate consequences if local manufacturing were to fail and shift to competing countries. The potential climate impact on downstream companies and individual consumers, who may find themselves with fewer EU-based choices, could create a greater uphill struggle for the EU in achieving its climate goals.

Nordea supports the climate transition towards more circular solutions in all sectors by offering a range of solutions and products to our large as well as small- and medium-sized corporate customers.

Register below for the latest insights from Nordea’s Sustainable Finance Advisory team direct to your mailbox.

Read more

Sustainable banking

Morningstar Sustainalytics has recently published a new report identifying companies that are taking steps to reduce emissions, set actionable targets and implement good governance practices. Nordea is highlighted for its significant progress in reducing emissions and its comprehensive climate targets.

Read more

Sustainability

Amid geopolitical tensions and fractured global cooperation, Nordic companies are not retreating from their climate ambitions. Our Equities ESG Research team’s annual review shows stronger commitments and measurable progress on emissions reductions.

Read more

Sector insights

As Europe shifts towards strategic autonomy in critical resources, Nordic companies are uniquely positioned to lead. Learn how Nordic companies stand to gain in this new era of managed openness and resource security.

Read more